Repost: WSJ, "What 1960s Antiwar Protesters Think..."

We need to (again) address the rise of protests against Jews, Zionism and Israel on college campuses. Masquerading as legitimate activism, these riots and ralleys are a stark betrayal of the values of true social justice. They unfairly compare themselves to the noble struggles of past activists, yet their actions speak of intolerance, hatred, ignorance, and above all else, excessive privlidge.

Let us not be deceived by the false narratives. These faux-activists are not champions of human rights; they are agitators calling for the destruction of my home, Tel Aviv, lending their support to some of the most heinous terrorist organizations in the world, from Hamas to Hezbollah, to whoever else vows to murder Jews. They champion ideologies that seek to obliterate the very existence of Israel and, by extension, half of the Jews. Their rhetoric is not one of peace but of destruction, echoing the darkest chapters of German history.

On our campuses, these groups have made it their mission to stifle dissent and intimidate visibly Jewish students. They have transformed universities into battlegrounds of hatred, reminiscent of the mobs that once upheld Jim Crow laws. Just as those segregationists sought to divide and oppress based on race, these modern-day hate groups seek to separate and vilify based on identity. We must stand firm against this new wave of bigotry and ensure that our campuses remain bastions of free thought and true equality.

Finally, some Vietnam Protestors were asked how they feel about the comparison of Israel’s defensive war against terrorist groups to protests against US involvement in Vietnam. To no surprise, most responders explicitly said they do not like the comparison, for reasons I’ll put in bold (mainly: they were the ones fighting in the war, they were peaceful, they were not calling for intifada and murdering Jews). Strangely, the two excerpts, who witnessed the Kent State incident, do not provide quotes as to whether they agree or disagree with the current protests. They give a general answer for all protests, regardless of if they’re protesting for abortion rights or against Jews on campus. My guess is the three reporters got tired of hearing that these riots are not anything like Vietnam protests, and are actually quite the opposite in intent.

Here is the original article: The Wall Street Journal - 1968 Anti-War Protesters and Pro-Palestinian Campus Protests There are some imagres there that I did not share because I refuse to put images of present day antisemites next to Vietnam protestors.

PS I wanted to include an article I found about college students appropriating the Keffiyeh, but it’s behind a paywall here: https://t.co/MVS8PfSHor These articles keep leaving out that the hipster swastika scarf is a Fatah symbol. A few years ago I condemned H@mas for beating Gaza students for wearing this symbol, banned in Gaza well before these students found out they could sport a scarf to voice their hate for Jews.

Ohio National Guardsmen preparing to advance toward Kent State University protesters on May 4, 1970. HOWARD RUFFNER/GETTY IMAGES

What 1960s Antiwar Protesters Think About Today’s Unrest on College Campuses

They protested a different war but say their demonstrations inspired much of the recent action

By Alyssa Lukpat, Joseph Pisani and Suryatapa Bhattacharya; May 12, 2024 5:30 am ET

Protesters on college campuses in the 1960s and ’70s are watching a familiar story play out.

Back then, student demonstrators denounced the Vietnam War and marched for civil rights. They made a long list of demands. Police arrested them. Today, pro-Palestinian protesters have disrupted campus life at universities across the U.S. They have their own demands, including colleges divesting themselves of investments in companies doing business with Israel. Thousands have been arrested.

The Wall Street Journal spoke to several people, now in their 70s, who participated in the antiwar protests more than 50 years ago. Some said they see themselves in this younger generation of protesters, while others drew stark lines between their actions and what they described as the violent language of demonstrators today.

IMAGE ON ORIGINAL ARTICLE Student protesters occupied Columbia’s Hamilton Hall in 1968 and in 2024. (DAVE PICKOFF/ASSOCIATED PRESS; JULIA WU/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES)

Both protest movements were divisive among the American public. Protesters opposing the Vietnam War clashed with those who felt it was un-American to criticize the war. Currently, students are at odds over some of the rhetoric coming from pro-Palestinian protesters and how some Jewish students feel unsafe on campus amid rising antisemitism.

Here is what several people involved in the Vietnam War-era protests said.

James S. Kunen, 75, New York

James S. Kunen, who was a sophomore at Columbia University in 1968, said he was proud to see protesters at the school again.

“It gives you a little rush of school spirit,” he said.

He protested the Vietnam War at Columbia because at the time, full-time students could be deferred from being drafted. He knew that meant someone else was in his place, either killing or being killed in Vietnam.

“I found that to be an intolerable situation,” he said. “I had to do something about it.”

He and other students took over Hamilton Hall in 1968, the same building on Columbia’s campus that pro-Palestinian protesters barricaded themselves into last month.

A photo posted to James S. Kunen’s Facebook page with the caption, ‘Me at Columbia 1968.’

Kunen, who wrote about his experience in the 1969 book “The Strawberry Statement,” said protesters eventually occupied five buildings over the course of a week, including the office of Columbia’s president. He ended up in the mathematics building.

“The police hauled us out,” said Kunen, who was arrested and spent the night in jail.

Kunen, who teaches English to immigrants, said he supports the current protesters.

“When something intolerable is happening like the slaughter of innocent people in Gaza, then it’s a good idea to step up and try to do something about it,” he said.

VIDEO NOT INCLUDED IN COPY: Many student protesters are demanding schools drop Israel investments. WSJ explores the history of divestment movements at universities and the challenges involved in modern divestment initiatives. Photo Illustration: Alexander Hotz/WSJ

Neal Hurwitz, 79, New York

Neal Hurwitz was a political science teaching assistant at Columbia in 1968. He said he was the youngest member of a faculty committee that was acting as a mediator between the administration and the student protesters.

Last month, when the police entered Hamilton Hall again to remove protesters, he walked to Columbia’s gates in support of Israel and the U.S. and against Hamas. He said he was opposed to how protesters caused damage in Hamilton Hall.

New York police entering Hamilton Hall in April 2024. PHOTO: CAITLIN OCHS/REUTERS

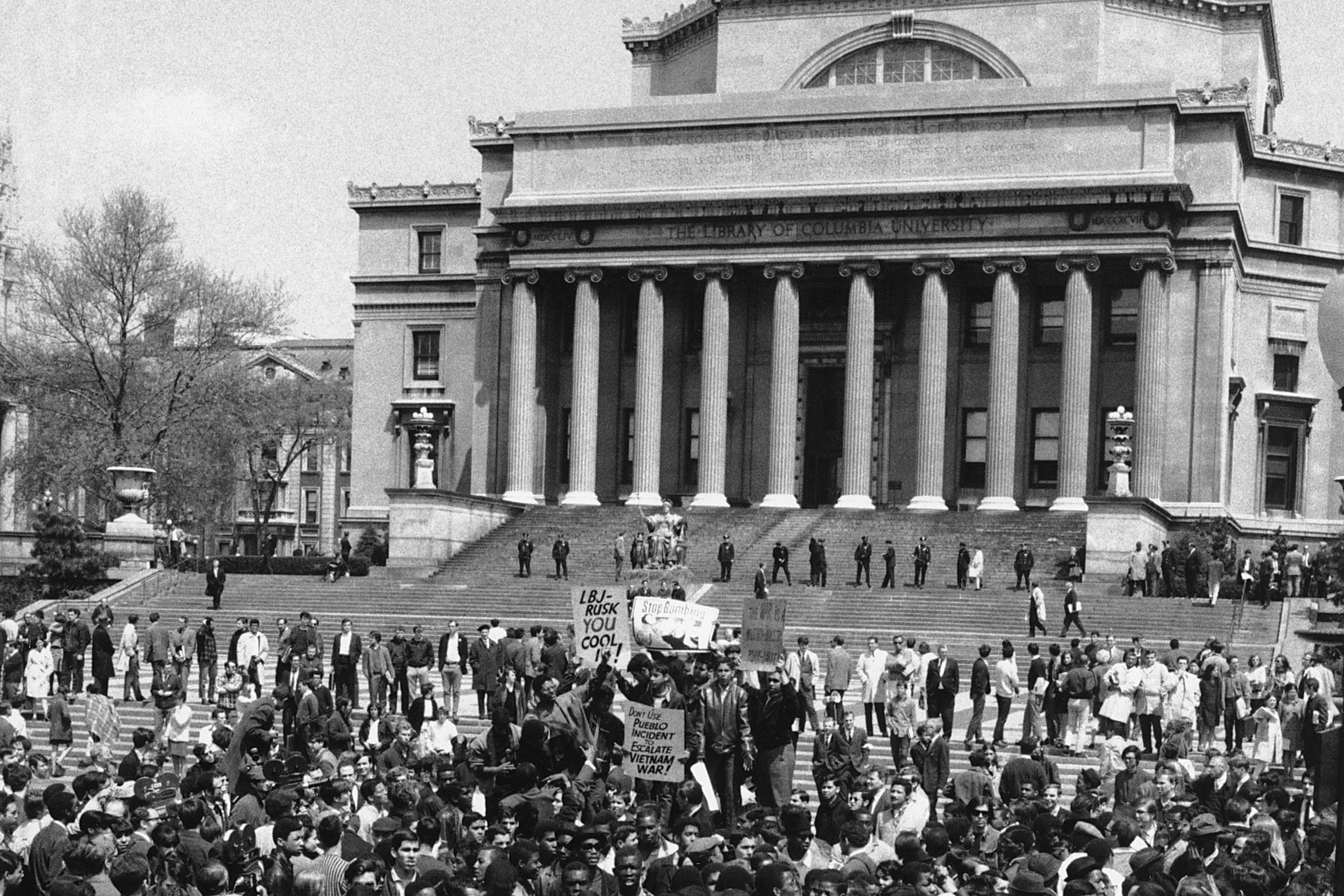

Demonstrators and students protesting in front of Columbia University’s Low Memorial Library in 1968. PHOTO: ASSOCIATED PRESS

The sounds from inside campus were familiar—the banging of drums, the chanting and yelling.

But he said the mood was remarkably different from what he had observed decades ago.

“The hatred, and the anger and the violence by words is really very intense,” he said. “There was a lot more intellectual and thoughtful thought in the ‘60s. Now it’s all emotional.”

The dispersal of protesters too, was different, he said. In 1968, many demonstrators were left bleeding after being beaten with bats on the head, he said.

“The cops are smarter now,” he said. “Maybe more humane?”

Linda Frey, 75, Maryland

Linda Frey remembers police using tear gas on protesters at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1969.

“We were just marching on campus,” said Frey, adding that some protesters threw rocks at windows, but many, like herself, were peaceful. “It was like a blanket response,” she said of the police.

Frey, a retired psychiatrist in Chevy Chase, Md., sees differences between protesters today and in the 1960s.

Many of them “don’t have direct skin in the game,” said Frey. Those protesting the Vietnam War, she said, were trying to keep their friends and family from being drafted.

National Guardsmen use a gasoline-powered tear gas machine to keep protesters away from businesses in Madison, Wis., in May 1970. PHOTO: PAUL SHANE/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Even so, she says, “there are issues of moral outrage in both situations.”

Frey said she has been disturbed by protesters using the word intifada, an Arabic word meaning “uprising” that Jewish leaders say is an incitement to violence against Israelis and Jewish people. She also worries about another slogan, “From the river to the sea,” referencing the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, which many Jews interpret as calling for the destruction of Israel.

“I don’t even think the kids fully understand some of the things that they’re spewing,” she said.

She says she doesn’t hear pro-Palestinian protesters mentioning the people taken from Israel as hostages during the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas.

“There’s no balance,” she said. “It’s bewildering.”

Steve Lewis, 74, California

Steve Lewis didn’t protest in 1968. He thought the best chance to end the Vietnam War was to help elect Robert F. Kennedy as president. He went door to door canvassing voters and talked up the antiwar candidate on campus.

“I viewed political activism as more productive than anything else I could do,” said Lewis, who was a student at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

A memorial to the victims of the 1970 Kent State University shooting on the school’s campus. PHOTO: GENE J. PUSKAR/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Kennedy was assassinated in June 1968, and Richard Nixon won the presidency later that year. The war went on. So Lewis, then at law school at the University of California, Davis, marched with other antiwar protesters at Sacramento’s State Capitol in 1971 and 1972.

He said he is grateful the current protests haven’t turned deadly, like they did in the shootings at Kent State University in 1970.

He does see a difference between the protesters now and then.

Lewis, a retired lawyer, said he has seen some protesters call for intifada.

“When we were protesting in the ‘60s, it was calling to save the lives of Vietnamese people and save the lives of American soldiers,” said Lewis, who lives in Sacramento, Calif. “Not to kill people.”

Donald Glascoff, 79, New York

Donald Glascoff, a retired Wall Street lawyer, said he attended many protests in the 1960s as an undergraduate student at Yale University and a law student at Cornell University. He wanted to observe them out of curiosity and wasn’t an active protester, though he said he opposed the Vietnam War.

“Protests by Yale students were basically all white, middle-class males,” he said. “This round, there are many more people of color.”

Donald Glascoff says today’s student protesters are much more diverse and organized. PHOTO: DONALD GLASCOFF

Glascoff said he was on the Yale and Columbia campuses during the recent protests and noticed the students involved were much more diverse, organized and prepared than the protesters from his generation.

“The ‘60s protests to me seemed to be more spontaneous,” he said.

The political tactics underlying some of the recent campus demonstrations came after months of training, planning and encouragement by longtime activists and left-wing groups, the Journal reported.

Glascoff said he disapproved of the Vietnam War in part because of his mother’s influence. Her family was Quaker, a pacifist Christian group. Still, he said in college he joined the U.S. Army’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps after his father died in part because he needed money. He never deployed to Vietnam because the war wound down while he was preparing to go.

Glascoff splits his time between a farm in Roxbury, N.Y., and an apartment on the Upper West Side. He has also produced an Academy Award-winning documentary.

Dean Kahler, 74, Ohio

Dean Kahler turned 20 three days before the shootings at Kent State changed his life.

He didn’t want to discuss what happened on May 4, 1970. He has recounted the story many times. The Ohio National Guard, called in by the governor, began shooting protesters on campus that day, killing four students and injuring nine.

Kahler told the university’s alumni group that he had never been to a protest so he decided to see what the one at Kent State was all about. Then the shooting began and a bullet tore through his spine, leaving him in a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Kahler said the shooting inspired him to get involved in politics. The governor who called in the troops, Jim Rhodes, and Nixon, the president at the time, were Republicans.

Dean Kahler says the shooting at Kent State University inspired him to get involved in politics. PHOTO: RAMI DAUD/KENT STATE UNIVERSITY

“They were responsible for my getting shot so I worked for the Democratic Party,” said Kahler, who lives in Plain Township, Ohio.

He said he worked for the Democratic Party in Athens County, Ohio, and for Anthony J. Celebrezze Jr., a former Ohio secretary of state and attorney general. From 1985 to 1993, Kahler was a county commissioner in Athens County. He has become a passionate advocate for voting.

“I have to get out the message that you have to be involved in democracy,” he said. “It’s not a spectator sport.”

Kahler, who is retired, said in his free time he likes to do half marathons in his wheelchair. He has done three full marathons. “I’m not 50 anymore,” he said. “A half marathon is easier to manage.”

Chic Canfora, 73, Ohio

Chic Canfora said it alarms her when politicians, including Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson, say they want the National Guard to handle college protesters.

“That is a striking and frightening parallel to what we experienced in 1970,” said Canfora, who witnessed the Kent State shootings that year as a student antiwar protester. Her brother Alan, who also protested, was shot in the wrist.

Chic Canfora says today’s student protesters give her hope. PHOTO: BOB CHRISTY

“I couldn’t go anywhere without hearing people talk about the war,” she said. “It was our generation being sent off to sacrifice their lives in even what the architects were calling an unwinnable war.”

Canfora, a professional harpist, is a journalism professor at Kent State and lives nearby. Many of her fellow protesters vowed never to return to the school, but she said she felt an obligation to be there and continue talking about what happened.

She says she advises student activists to be peaceful and to be on guard for provocateurs who may infiltrate their ranks, as some have done in other protest movements. Overall, the student protesters give her hope.

“I’m inspired by these young people and I hope they don’t give up seeking peace in the Middle East,” she said. “Our students are being what we were 54 years ago: The conscience of America.”

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How would you compare 1960s antiwar protests to today’s campus demonstrations? Join the conversation below.

Write to Alyssa Lukpat at alyssa.lukpat@wsj.com, Joseph Pisani at joseph.pisani@wsj.com and Suryatapa Bhattacharya at Suryatapa.Bhattacharya@wsj.com